TASTE GLORY

"The hardest part of winning gold was waking up the next morning and realizing you're still the same person you were the day before."

You may not know Herb Perez’s name, but to me, the 1992 Olympic gold medal Tae Kwon Do champion was a big deal. Competitive martial artists you’ve never heard of like Christine Bannon-Rodrigues, Jimmy Pham and David Douglas were very big fish in my teenage pond.

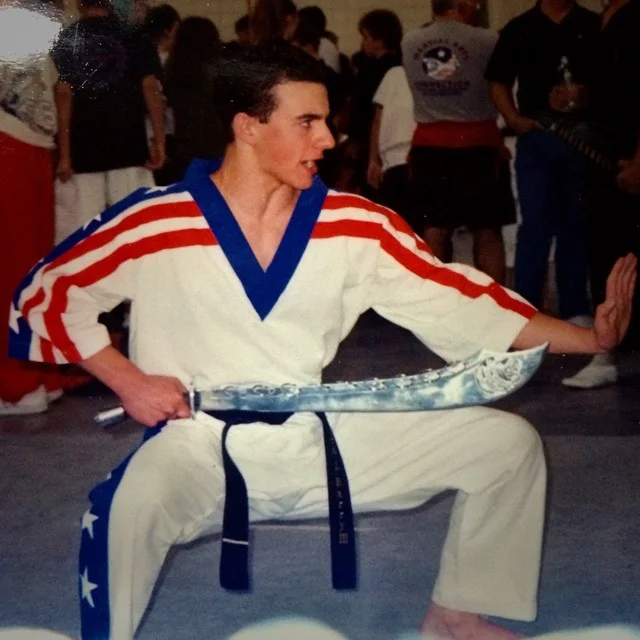

I admired them because I competed, too. At my best, I was never better than second-tier, but I collected enough third and fourth-place trophies from the bigger tournaments to get my hopes up, to keep me coming back again and again. I spent weekend after weekend competing with a bunch of people who were pretty average, a handful who were my peers, and always one or two or three who were beyond my reach: they sprang forward just a bit faster. My blocks were just a little too stiff. Their posture was just a little more relaxed. I was a just half an inch higher than I could manage, just a little less on balance, and on and on. I was good. They were memorable. I was reliable. They were exciting. I was solid, respectable. They were beautiful.

“ I was good. They were memorable. I was reliable. They were exciting. I was solid, respectable. They were beautiful.”

For me, the distance between B-list and A-list was tiny and uncrossable. I wasn’t a natural athlete, but every day, I would go to my karate studio, practice for a half hour or an hour, earn some money by teaching the younger students for a few hours, then take a class, go home, and start whatever homework was due the next day. The work I put into practicing in the afternoons and taking classes in the evenings got me just close enough to the A-list to realize that I couldn’t get there.

I still wanted to, though.

I thought a lot about what Herb Perez said when I took that class with him a few years earlier, about the crushing disappointment that set in the morning after winning, about realizing that even though he had won the gold and new opportunities were about to open to him, nothing in him had changed. I even understood what he was saying. I just didn’t care.

I wanted to be featured in the champion’s exhibition at the end of the major tournaments. I wanted to know that I had done things within my small world that had made an impression on people, that were worth remembering. And most of all, I wanted to be at the after-party. I wanted to be with people I knew mattered, and I wanted to be celebrated and stand celebrating alongside them. I wanted it so badly that it’s what I wrote about in my creative writing classes at school—hazy vignettes about martial artists being celebrated by their peers after once-in-a-lifetime performances. The vague existential dread that apparently came with it seemed like a pretty good problem to have.

I retired at 16. I had done well enough at a qualifying tournament to be invited to be a warm body on the back bench for the ad-hoc US team at the 2000 Martial Arts Millennium Games in Sydney, Australia—the first event to be held in the Olympic arenas. If I wanted a chance to scrape the bottom of the A-list, this was it: I could skip my AP exams and go to Sydney. When I came back, I’d be able to pique the interest of a dedicated coach. I’d have to take easier classes in school and stop teaching, but with maybe a year of solid work under the right coach, I might be able to start counting on first in regional competitions and at least third in national ones.

Or I could finally listen to the advice I had gotten years earlier, admit that winning wouldn’t re-define me, and live a normal life.

I think I made the right decision, but here’s the thing: If winning wasn’t going to change me, stepping away from competition wasn’t going to, either. Years later, I was working in politics and I was dealing with the same dynamics: if I could just write a speech that was good enough to get air time, if I could just get a bill passed, if we could just get an election won, there would be glory on the other side.

Working in politics can be pernicious: Every little world offers its own promises of affirmation and celebration if you can just reach far enough, work hard enough, dig deep enough, win enough. But politics is one of the few fields that offers the possibility of commemoration that isn’t provincial. Being a recognized name outside of your industry or sub-culture is usually reserved for the rarest exemplars in a field, the kinds of people who come along fewer than once in a generation: Steve Jobs. Alfred Hitchcock. Bruce Lee. Politics and government, on the other hand, offer more opportunities to leave a recognized mark on the wider world than most other fields. Your work can change people’s lives. And if you navigate things just right, people might even remember your name when they think about what made their lives better, easier, more joyful or more productive. Give the right speech–or write the right speech–and your words can shape a party or inspire hearts for generations to come.

My first campaign was for a long-shot candidate in a primary race, and we lost. That was fine. Like I said, we were a long shot—and I had had years of practice being a runner-up. But my second campaign? We won big. Largest-margin-of-victory-in-the-country-for-any-seat-that-changed-party big. As my staff and I were driving to the victory party, I was all nerves and anxiety. Why weren’t we there yet? I wanted to be in the celebration. I wanted a taste of the glory and esteem that always seemed just outside the realm of possibility for me in my former life. We got there and, frankly, it’s a blur. I know I drank cognac for the first time, I think I was on the matador end of a bullfight with one of my colleagues, and I got a lot of pats on the back for driving up our vote margins.

But the glory of the after-party didn’t last. The next day, I went back to my office and worked on close-out. I found another job with new targets to hit, and I failed at some of them. The next election cycle, the urgency of the present made it harder for people to remember our campaign. The guy we got elected was out of office by the end of the next wave year.

After the after-party, you still have to live your life. My first campaign victory maybe should have been enough to get me to understand that—I was a Christian by then, and knew in theory that I was waiting for God to inaugurate a better Kingdom than anything we creatures could cobble together ourselves. I knew that my name was written in a record book from which it can never be erased and in which it will never be lost in the crowd. But the funny thing about the Christian life is that you have to keep learning the same lessons over and over again, internalizing the same messages more and more deeply each time. My first campaign victory brought me face-to-face with Herb Perez’s warning. Years later, I’d have to confront it again—when I actually got to go to the very after-party I’d fantasized about in my former life.

Last summer, my wife and I went to watch a karate tournament that was part of the national circuit on which I used to compete. While we were watching the champion’s exhibition, someone walked by and handed us two tickets to the VIP after-party—reserved for small-pond celebrities like grand-championship winners, major coaches, and other select guests. We still don’t know how or why the tickets ended up in our hands, but of course we went. And we spent over a half-hour in a private booth talking with Christine Bannon-Rodrigues—who you may remember from paragraph two—and her husband, Don Rodrigues–the coach who elevated two of my peers to the A-list and who at one point or another coached every last one of my greatest teenage idols.

We swapped war stories, he talked about the future of the circuit and he waxed nostalgic about the history of his team. It was the Valhallic glory I craved as a teenager. When my wife and I left, I was beaming. I got to feel even cooler when my wife ran into two attractive college students in the ladies’ room who had traveled four hours from out-of-state to watch the tournament. They wanted badly to visit the after-party, and my wife suggested we give them our passes, since we were leaving. Why not share the wealth? Why not get to feel magnanimous?

I went to bed that night grateful for an experience I’d wanted most of my life. When I woke up the next morning, maybe because I had been primed to look out for it, I was acutely aware that it hadn’t made me perfect.

“What I want from the after party is offered by Jesus when he invites sinners and idolaters to join him at Abraham’s table. ”

What I want from the after-party—welcome, celebration, camaraderie, an assurance that something I did was worth noting or that something about me might be remembered—doesn’t really come from reaching the lofty heights of a Jon Valera or a Richard Brandon or a Jamie Webster. And it doesn’t come from a signature piece of legislation bearing your name for the fifteen or twenty or fifty years that it’s relevant. But it is offered by Jesus when he invites sinners and idolaters to join him at Abraham’s table—and it was guaranteed by God when he raised Jesus from the dead as proof that what he promises will be delivered. What I’ve been hoping for from an after-party, I know I’m getting at the Wedding Supper of the Lamb—life’s real launch party.

Rick Barry is Executive Director of the Center for Christian Civics. He has worked on campaigns for local, state and federal office, is a former writer and editor for Redeemer Presbyterian Church in New York City and oversaw communications for the Grace DC church network in Washington, DC.

LIBERATUS is a weekly journal creatively pursuing Truth and Beauty by empowering writers in American politics to tell the story of healing through freedom. You can join the pursuit by applying to write, subscribing to the journal, or by funding the movement through monthly giving or by making a purchase in our store.

When you pick up an iPod, or an iPhone or an iPad, you know immediately and intuitively that you’re holding a work of art, a carefully crafted device likely surpassing all others in its field. What will it take, then, for politics to become a work of art, reflecting honest craftsmanship?