Live Your Passion

Last week, we looked at the theme of the London 2012 Olympic Games, “Inspire A Generation,” and tied it to the theme for Rio: “Live Your Passion.” We continue the same topic this week, after concluding last week that living your passion requires you to come fully alive.

It’s also worth repeating the disclaimer from last week: The topics and ideas we are covering this and last week are heavy; we’re diving deep to try to get to the bottom of what it means to inspire a generation and to live your passion. They are two Olympic themes that I think are inextricably linked, and while today and last week mark an attempt to trail blaze through a pile of ideas and books, I know I need to offer these thoughts with open hands, and an open mind. I’m dealing with so many ideas that I can’t claim to know the ultimate conclusions of all them! Nevertheless, there are ideas here we need to journey through to see freedom at a deeper level, to stumble upon great wide open space, to learn how Truth and Beauty can be reflected in our work. We talk about “creatively pursuing Truth and Beauty,” as opposed to achieving, establishing, owning, using, standardizing, scoring, or upholding Truth and Beauty because they can eternally be pursued, but we will continually fall short of doing anything else! It helps to read one of Richard Rohr’s Daily Meditations, in which he notes that “eventually we must move from exclusively trying to solve our problems to knowing that we can never fully resolve them, but only learn from them. Sometimes, we can only forgive our imperfections and neuroses, embrace them, and even ‘weep’ over them (which is not to hate them!) This is very humbling for the contemporary Promethean individual.”

After looking at two of the five points last week on how to truly live your passion, we continue with number three:

3. Arguments against pursuing your passion are actually arguments in favor of pursuing your passion.

3.1. "You might suck at it."

I've heard this one recently from Mike Rowe, of all people.

But the solution is pretty obvious here: "Yes, and I'm going to work hard and get better." People aren't static, and we shouldn't treat them as if they are, especially if they are working out of a genuine intersection of their unique talents, their passions, and a great need in the world.

And if you can’t get better at it, maybe you actually were just chasing an idolized dream and not a gifting, passion, or need in the world. If we’re going to come fully alive, and live authentically, as we mature we will hopefully learn to know the difference. Additionally, what does "suck at it" mean? In his video on the subject, Mike uses the example of all the people who audition for American Idol but never make it. Does that mean they weren't "successful"? Hardly. We've got to get over our view of success as a huge following and lots of money. Neither of those are necessarily success. If you’re a follower of Jesus, we have a calling to bring restoration to this world, and the humility it takes to truly do so may never look like success, because our calling is to tell of an entirely different Kingdom with values far different from the current hierarchies of power and status. True success is in part seeing reality at a deeper level, and working to make Truth and Beauty the defining characteristics of our work will rarely align with the ways we currently lead, communicate, and value personal well-being in politics.

Even if we’re not thinking of success in light of the Kingdom, success still requires taking every day steps to meet a long-term vision. Someone who gets made fun of pursuing their passion might have needed that step as part of their growth, or to rediscover a different outlet for a musical career, or any number of outcomes. For some people, just showing up on the proverbial stage of American Idol is a success that will lead to continued success later in life.

3.2. "Just do your job well."

I think the logic goes something like this: "Don't be obsessed with finding your dream job; just work to earn a paycheck." But thinking holistically, this is too simplistic. We really shouldn't separate pursuing or living our passion from whatever opportunities are in front of us. Pursuing our passion is too often made out to be something elusive, as opposed to something that's right in front of us for the taking. This is not an either-or scenario. Going back to the Mike Rowe video, he touches on this with his conclusion: "Never follow your passion but always bring it with you".

On this point, the idea that you should just "do your job" and not worry about your passion is misguided because it ignores the fundamental need of humanity in any work environment: to be creative and invest themselves wholly into their work. I think we too often create hierarchies, defining work as either exciting or non-exciting, forgetting that the dynamic we should be after is work that is beautiful or not beautiful. I think this is especially true for followers of Jesus, because our work in the Kingdom won’t be boring, and the fun work won’t be reserved for the select few at the top of a non-existent hierarchy. By relegating some work to being "mundane" or "grunt work", we miss the insights and innovations and creative potential that people have to make revolutionary breakthroughs in those supposed mundane tasks. We miss that all work can become beautiful art.

And if all work is art, then having a coherent answer to "what is your passion?" is mandatory. As Steven Pressfield notes in The War of Art, viewing your work as art both shakes up the hierarchy of work and the reason for it:

For the artist to define himself hierarchically is fatal. (p. 150)

To labor in the arts for any reason other than love is prostitution. (p. 151).

As we approach the Games of the XXXI Olympiad, we can see both a breakdown in hierarchy and work for the love of the pursuit in athletes. In The Golden Rules, Bob Bowman, the head swim coach for Team USA, shares the kind of thinking Dr. Jim Bauman, a sports psychologist, will share with swimmers who are struggling to focus at the height of competition:

"Your job is to swim as fast as you can between point A (the start) and point B (the finish). Swimming fast has nothing to do with your opponent or a medal. It is important to focus on your job and what is relevant to swimming fast—your race plan and the technique of your stroke. Medals, money, your heat, your lane, other swimmers, social media, the media—they're all sources of irrelevant noise that will only slow you down. If you pull in all the irrelevant stuff, it will make things chaotic for you. Keep it simple." (p. 220).

Finally, if you are a follower of Jesus and you still aren't convinced that your work can be turned into art, consider what Tim Keller says in Every Good Endeavor:

The gospel frees us from the relentless pressure of having to prove ourselves and secure our identity through work, for we are already proven and secure. It also frees us from a condescending attitude toward less sophisticated labor and from envy over more exalted work. All work now becomes a way to love the God who saved us freely; and by extension, a way to love our neighbor. (p. 73).

In the Christian view, the way to find your calling is to look at the way you were created. Your gifts have not emerged by accident, but because the Creator gave them to you. But what if you're not at the point of running in the Olympics or leading on a world stage? What if you're struggling under an unfair boss or a tedious job that doesn't take advantage of all your gifts? It's liberating to accept that God is fully aware of where you are at any moment and that by serving the work you've been given you are serving him.

When your heart comes to hope in Christ and the future world he has guaranteed—when you are carrying his easy yoke—you finally have the power to work with a free heart. You can accept gladly whatever level of success and accomplishment God gives in your vocation, because he has called you to it. You can work with passion and rest, knowing that ultimately the deepest desires of your heart—including your specific aspirations for your earthly work—will be fulfilled when you reach your true country, the new heavens and new earth. (p. 241)

Robert McKee talks about writing the truth, so that your own heart starts pounding. Since I know many of the readers of the Liberatus journal have ties to Congress, here goes: I have yet to meet or talk to a single person, at any level, who says they enjoy, love or are passionate about constituent mail. And yet, congressional offices send and receive thousands of pieces of mail every year. This is a problem.

In Congress, roughly 25-year-old Legislative Correspondents are hired to write letters in response to literally hundreds of pieces of mail that come in every day, at salaries averaging $35,000. And for the sake of comparison, a 2nd Lieutenant in the U.S. Marine Corps stationed in the Washington, DC area, with no dependents, receives $25,000 annually just to pay rent, on top of a $35,000 salary (assuming less than 2 years of service at a base pay grade of O-1). The point here isn’t to complain about what people in the military get paid: they should likely be getting paid more, if we’re truly thinking about what we ask them to do. What we need to see is that we don’t adequately value the work, elevate the communication, or compensate the people who are tasked with making America function as a Democratic-Republic.

If you've wondered why Congress has such abysmal approval ratings, wonder no longer. We don't value the work, and we aren't passionate about it—rather, we are passionate about moving "up" where you don't have to be tasked with "lesser" work. The result is that correspondents are largely forced to write canned responses no one wants to read. Or, perhaps it is the other way around: we don’t value Truth and Beauty in our work, we don’t value leading well or authentically, so we force hundreds of twenty-somethings (for as long as they choose to accept the job) to write boring letters that sound canned to the writer and reader—and that’s why no one is passionate about the work. We’ve taken any possible joy out of it to the point where “doing the mail” is too often a phrase used synonymously for “perpetuate nonsensical chaos.”

Now, I know from experience that this is not always the case: when I worked on the Hill, I did my best to write letters that communicated something worth reading. It can be done, but to do it well, to see this as art, we're going to have to think different.

All of that said, to continue looking at how arguments against pursuing your passion are actually arguments in favor of it, here's our next idea:

3.3. "I don't even know what my passion is."

Really? You've worked thirty years in the corporate world and never once discovered something you enjoy? You aren't living passionately, ever? Yet people say this like it's noble how they've just "applied themselves" instead of recognizing the tragedy of it. And how would this type of thinking work in other areas of your life? "Don't pursue someone to marry that you're passionate about, just pick the best opportunity!" What?

What we're after is merging the two, and I think anyone who says they don't know what their passion is either has many, which is reasonable, or has been living it all along and didn't realize that being "passionate" meant depth and hard work and focus, rather than the straw man we create of lazy-dispassionate-hipster-organic-food-eating-millennials-in-skinny-jeans-and-weird-hair. But we've got to stop demonizing people for wanting to pursue their passions. They don't need to pursue them less, they need to pursue them better, and anything less is dehumanizing.

And that note brings us to our 4th main point about living your passion, which includes several sub-points.

4. Truly pursuing your passion will bring order, not chaos.

4.1. Bring what you love to your work.

Bob Bowman is a swimming coach who loves to help athletes achieve their goals. Because he is able to bring that love to the sport of swimming day-in and day-out, Olympic cycle after Olympic cycle, he's also able to think outside the box. The boundaries for what one assumes can be done are broken in many ways. Consider the impact of his work through the story of a swimmer who wasn't performing well under his program, who logically should have been cut:

Throughout her competitive career, Cierra had primarily been a sprinter. Nothing surprising there. Swimming tradition held that tall kids made for good sprinters. But the way she swam, with long, languid strokes versus the rapid, pulverizing ones of a sprinter, got me thinking: Maybe she's better suited to longer distances. (The Golden Rules, p 71).

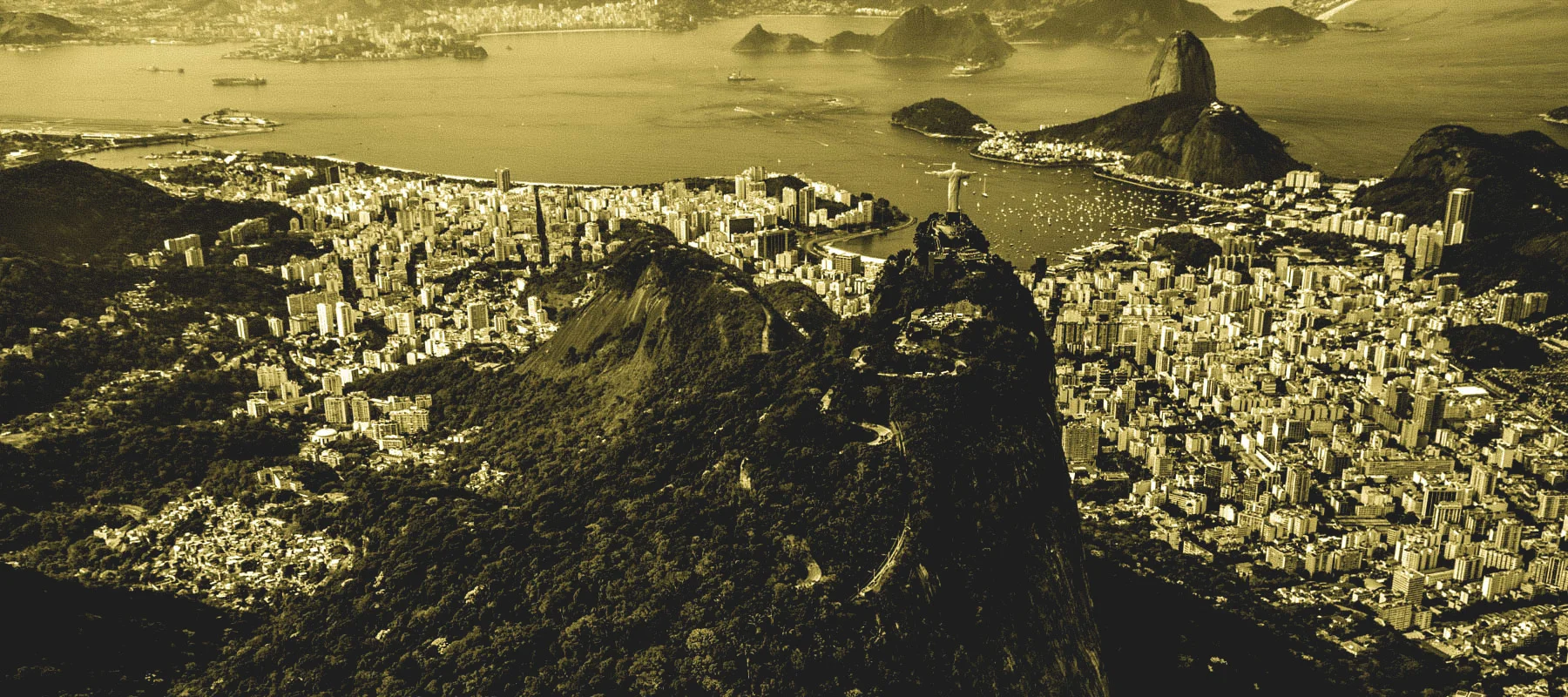

He goes on to detail the result: she became a highly sought-after recruit for college programs, went to UC Berkeley, earned a new collegiate record for her school by swimming the 500-yard freestyle, and now (at the time of this writing) has a real chance to step onto the podium in Rio De Janeiro.

If you bring what you love to your work, inevitably you're going to wind up helping other people in your workplace.

Cheryl Bachelder writes about developing other leaders, and I love a question she poses on the topic: What could be more challenging, more demanding, or more valuable to a developing leader, than developing a plan to become the leader they most admire?

Sam Wyche is another sports figure we can learn from. I heard him speak when I was working in Congress, and although I don't remember all of his advice, I remember one point very well:

4.2. Finish what you start.

I've never forgotten it. Following your passion, pursuing it, living it, however you describe it, means you should actually pick something and finish it. Of course, that does raise the question: what if I get my passion wrong?

Clearly, there can still be a "finish" point to whatever it is you're doing. Additionally, living your passion doesn't mean jumping into something on a whim.

4.3. Learn what your passions are while you grow.

Jump in and start working, because you'll gain experience and insight and perspective, both on your passion and on how to live it well, no matter the circumstances.

4.4. Find innovations.

When we turn workplaces into clock-in and clock-out cultures, we disallow people to innovate beyond the strict guidelines of clock-in and clock-out. I know by saying this, though, that this idea would lead us to reimagine huge portions of our economy—but that itself might be incredibly life-giving! When the Kingdom is fully established on a restored earth, I don’t think a staple of a restored world will be fried, non-nutritious junk served by teenagers employed at fast food chains.

4.5. Mature beyond being star-struck at your place in the world.

I think this last point is especially helpful for people working on Capitol Hill. It's great to appreciate representing thousands of people for your job, and the hard work of creating a republic every day. But still, if you are in awe of being there, you're probably never going to see what's broken and begin fixing it. You'll be way too impressed by your place in the hierarchy among the marble columns and therefore too unfocused to see your work as art, or too blind to find major innovations and fix major problems. Happiness in your work shouldn't come from ignoring what needs to be done to improve.

Now we're ready for the fifth and final point on what it truly means to live your passion.

5. Passion means suffering and suffering means new desires.

I recently stumbled across an e-book called Jump Start: 7 Lessons I Learned While Making My First Million, which you can download from Dale Partridge,*** (see note on March 26, 2024 below) founder of StartupCamp. He describes living your passion, or living his passion, this way:

I’m a victim of passion. I live with such fierce vision, ideas, and desires that it actually hurts. My chest burns. My thoughts storm. My feet begin to tap. On many occasions, I can’t sleep or I chase my thinking into the night. Or my mind becomes consumed with images of what could be. Images so real and so important that doing anything else in that moment seems irresponsible.

If you look up the original definition of the word “passion” in any standard dictionary, you’ll find it’s defined as: To endure suffering. Interestingly, the word was first used in the late 12th century to describe Christ’s willingness to suffer on the cross.

Since then, the word “passion” has been hijacked. Misused and abused. Reduced by a feel-good culture chasing simpler language and simpler definitions. Today, passion is understood as “what excites you” or “what puts the sparkle in your eyes, the twinkle in your toes.”

But passion is so much more.

Passion is the willingness to suffer for what you love. It’s an experience to be coupled with words like pain, preparation, readiness, submission, and loyalty. It’s the heartbeat of our calling and the soil of which dreams are grown.

But more than that, passion is complex. It’s one thing to suffer and be a victim; it’s an entirely different thing to be willing to suffer for a vision and become a victor.

When we discover what we are willing to pay a price for, we discover our life’s mission. (pp. 6-8).

***Update on March 26, 2024: This quotation, and entire e-book, may have been plagairised. Christianity Today has outlined Dale’s prolific use of material not his own. A google search of the text above reveals the author may have been Sandile Shabango. We have the PDF with Dale’s name on file, and apart from the title page and author, it’s identical to work also published by Sandile in 2016.

Discovering our life's mission. It's a beautiful idea. And when it's in line with the Kingdom, it's not ambiguous. Suffering means new desires, because suffering means a fake reality is dying, and we are awakening to new life. We have to see beyond shallow identities, which were perhaps created out of our woundedness, to the true grit of following Christ.

Richard Rohr breaks apart our thinking well in his devotional from June 15, 2016:

Almost all of us start with a performance principle of some kind: “I’m good because I obey this commandment, because I do this kind of work, or because I belong to this group.” That’s the calculus the ego understands. The human psyche, all organizations, and governments need this kind of common sense structure to begin.

But that game has to fall apart. It has to, or it will kill you.

One of the only ways God can get us to let go of our private salvation project is some kind of suffering.

Suffering opens our eyes to new life; the more we catch it, the more we can and should charge forward with deeper and widened perspective. This maturity, ultimately, is what it means to live your passion. We are given new passions, better passions. Passions that we will live forever.

Therefore, preparing your minds for action, and being sober-minded, set your hope fully on the grace that will be brought to you at the revelation of Jesus Christ. As obedient children, do not be conformed to the passions of your former ignorance, but as he who called you is holy, you also be holy in all your conduct, since it is written, "You shall be holy, for I am holy." And if you call on him as Father who judges impartially according to each one's deeds, conduct yourselves with fear throughout the time of your exile, knowing that you were ransomed from the futile ways inherited from your forefathers, not with perishable things such as silver or gold, but with the precious blood of Christ, like that of a lamb without blemish or spot. (I Peter 1:13-21).

But the story of forever isn't one we have to wait to start writing. We've already outlined how to live passionately, and do it well. The Kingdom is already and not yet. We can pursue life and restoration from the wounds we've been dealt, whether big or small.

Last week, I noted the abuse Mark Bouman endured as a child, which he recounted in The Tank Man’s Son. As an adult, he wound up working at an orphanage in Cambodia. The country crashed into war, and he found himself in the gut-wrenching position of saying goodbye to his family while they fled the country, and returning to Cambodia and the orphanage.

"Papa, Papa, Papa!"

The kids had been hiding inside the buildings, cowering in fear. Now their shouts of disbelief and relief announced them as they streamed out from all sides, streaking toward me across the grass like fireworks. (p. 335).

A father to the fatherless, prepared to care for these children by the apathy and evil of my own childhood. I was my dad, but changed—turned inside out by grace and granted a chance to redeem the past. I was Papa.

"You're back! You came back!"

"Papa, you're back, like you promised!"

"We didn't think you'd come back, Papa, but you did!"

Joy was in flood, and I was drowning in it. Every word healed me. Every word left me wanting more. (p. 336).

Our work in politics just doesn't have to be one of strident fear and anger. We can bring what we love to our work. We can make beautiful art. We can empower others to do the same. The depth of healing that's possible is staggering.

"God loves us!" [Paul] wrote from prison. "Nothing can ever – no, not ever! – separate us from the Never Stopping, Never Giving Up, Unbreaking, Always and Forever Love of God he showed us in Jesus!" (The Jesus Storybook Bible, p. 340).

In all of our wanting, all of our desires, all of our suffering and rebirth, we can live our passion in whatever art we create, because we were loved first.

LIBERATUS—we are set free.

WEEKLY ACTION ITEM:

What aspect of American politics is causing you pain? Is the tension of seeing what is and what could be your calling to bring healing? We'd love to hear from you. Write to us using the form below and let us know.

LIBERATUS is a weekly journal creatively pursuing Truth and Beauty by empowering writers in American politics to tell the story of healing through freedom. You can join the pursuit by applying to write, subscribing to the journal, or by funding the movement through monthly giving or by making a purchase in our store.

The Olympics can give us a glimpse of what it means to be fully alive, especially if you see the athletes compete in person. The theme of London’s games was “inspire a generation,” and the theme of Rio 2016 is “live your passion.” I think the way to inspire a generation is to live your passion; this week and next, we’re taking a deeper look at both Olympic themes.